Motivation The Most Effective Way To Motivate Someone On The Autistic Spectrum

The AE Team

The Issue Isn't That They Are Unmotivated (Here's Why)

In my experience, most people that manage to roll themselves out of bed in the morning and engage in some activity besides staring at a wall all day are motivated people. How do I know that? Because they’re moving with a purpose.

Psychology has a much broader definition for motivation than most of us. Someone might think of the motivation behind a morning jog as the desire to be happier and get in shape. However, a psychologist would want to add a few more things to that list of possible motivations.

You might run because:

- You’re late and you’re in a hurry

- A tiger is chasing you

- You’re afraid if you don’t, then you might die of a heart attack someday

- It’s cold, and you want to get inside quickly

- You want to be fast enough to join the track team

- Your friend told you that if you run around the block barefoot he’ll give you $5

- The list goes on...

Motivation is anything, internal or external, that moves you to action. It doesn’t have to be a high-minded internal desire, and the action doesn’t necessarily have to be something productive. Motivation can be an instinct, a biological urge, an emotion, a reward, a punishment, a habit, a compulsion, you name it.

Why am I telling you this? Well, your child is probably rolling out of bed and spending their time doing something (like video games, for example). If that’s the case then, believe it or not, the issue is not that they’re unmotivated. The issue is just that they don’t have motivation to do the thing you want/need them to do (like their homework that’s due tomorrow). As it so happens, that is a much easier problem to solve.

Two Kinds of Motivation

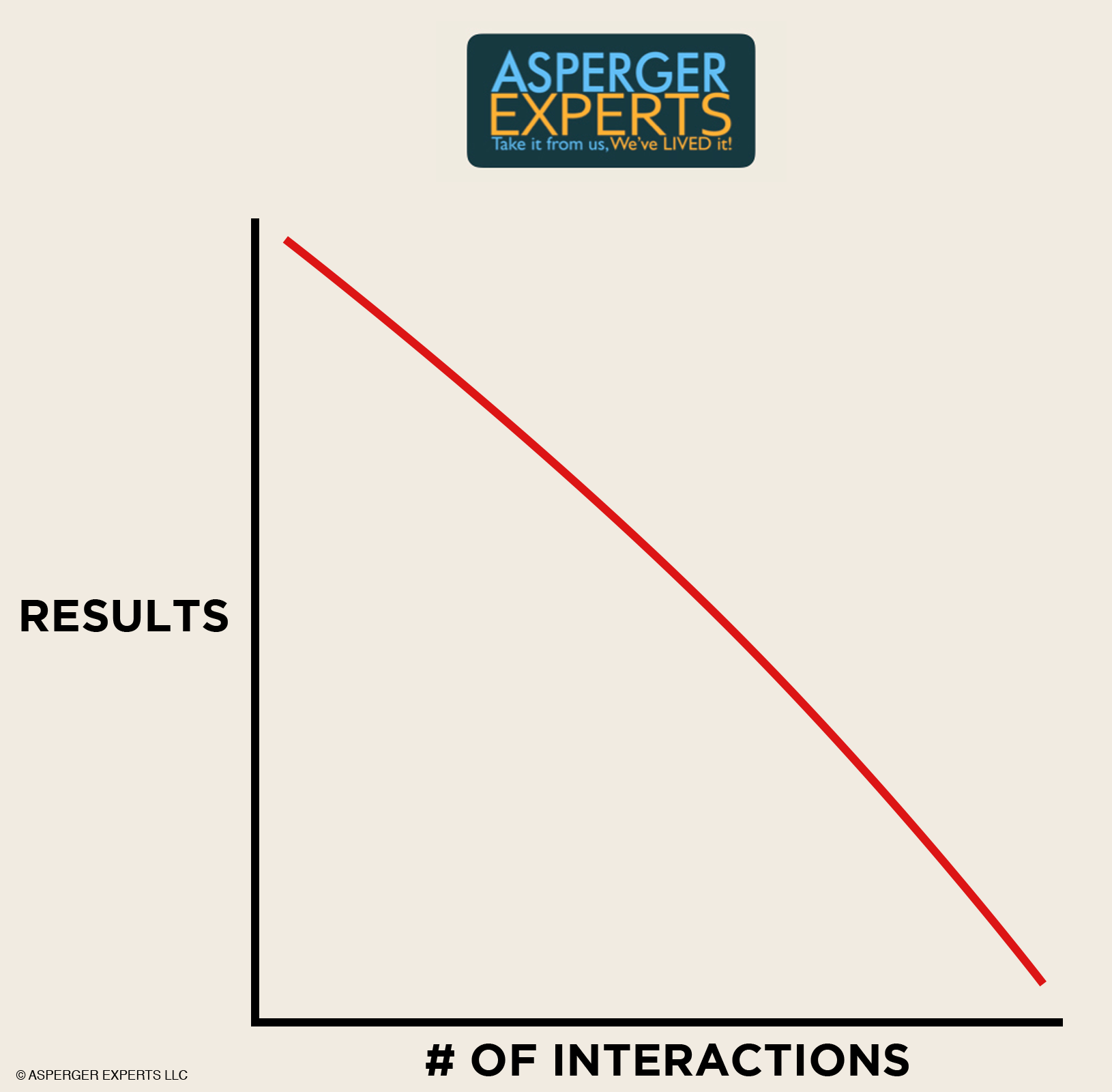

Here’s a graph for you to look at.

Isn’t it lovely? This particular graph illustrates one of the two major approaches to motivation: Red-Line.

(Editors Note: Watch a video explaining this concept here.)

Let’s break it down. On the X-axis (horizontal) we have the number of interactions. That’s simply the number of times you’ve attempted to motivate someone. When the red line is on the left-hand side, that means that there have been very few interactions and not much time has passed. When it’s more towards the right, that means that there have been many interactions and more time has passed.

On the Y-axis (vertical) we have results. This is simply the thing you’re trying to accomplish. When the red line is closer to the top the results are high, life is great, and things are happening. When it’s closer to the bottom the results are minimal or non-existent. Sometimes the results can even be the opposite of what you want.

Make sense? Cool.

Red-Line motivation is by far the most commonly used kind of motivation out there. A Red-Line Motivator’s go-to question is, “What can I do, give, or take away that will produce a result (a change in behavior) now?” Red-Liners love carrots and sticks, rewards and punishments; it’s all about control.

If a Red-Liner wants you to do something, then they will find the sweetest carrot they are willing to give and dangle it in front of you until you start chasing after it (money, video games, love and acceptance, etc.) Alternatively, they will find the scariest punishment they can and throw it at you until you move (losing privileges, yelling, withholding love and affection, etc.) They will bribe, manipulate, control, and coerce you to try to get you to do what they want.

Basically, Red-Liners seek to reduce human motivation to its most basic elements. They assume that people avoid pain and effort, and that they will only work hard if moved upon by an outside force or a biological urge (hunger, sleep, sex, etc.) Red-Liners see human beings as little more than animals responding to stimuli. Trained rats in a cage will press a lever over and over if you give them food. A yappy dog with a shock collar can be conditioned to stop barking. Similarly, a Red-Liner believes that you can motivate humans by tapping into that same desire to avoid pain and seek out pleasure.

And it works! If you offer to give your potty-training toddler a piece of chocolate every time she successfully uses the toilet, then she will start going to the bathroom more consistently. If you incentivize your employees with substantial bonuses, they will work harder to get that payout. Alternatively, if you put the fear of God in your teenager before handing them the car keys, they will likely drive more cautiously. If your boss tells you that the next person who turns in a late report will be fired on the spot, you will see tardiness rates drop significantly.

Psychologists have known for nearly a century that people will respond to the right rewards and punishments (they call it conditioning). Meanwhile, kings and rulers have understood this basic truth for millennia. You have to admit, it’s a rather elegant idea. If you want more of a particular behavior, reward it. If you want less, punish it.

However, nowadays we have decades of scientific research showing that the carrot-and-stick philosophy we hold dear actually has quite a few holes. Parents, teachers, and managers are gradually discovering that people, particularly people with Asperger’s, don’t always respond to external influences in the ways we would hope or expect.

What’s going on there? Well, as awesome as carrots and sticks can be, they come with some pretty serious drawbacks.

Problems with Red-Line

Let’s pretend, for a moment, that you were suddenly in a tragic accident that caused you to be irreversibly paralyzed from the waist down. No more walking, running, jumping, or wiggling your toes. Would you be sad and upset? Would you be sad and upset for a long time? How about for the rest of your life?

Now, let’s try another question. Imagine that today you win the lottery in the amount of ten million dollars. And, because this is your imagination, let’s say that you receive all of this money tax-free. Would you be significantly happier? Would you be happier for a long time? Would you go so far as to say that you would be happier for the rest of your life?

In both of the examples above, you probably assumed that their effects on your emotional well-being would be significant and long-lasting. And that’s where you would likely be wrong.

In a classic 1978 study, three psychologists investigated and measured the happiness levels of paraplegics and lottery winners. They found that less than a year after experiencing one of these life-changing events both the lottery winners and the paraplegics had mostly returned to their baseline levels of happiness. We would normally expect lottery winners to be much happier than regular folks. However, they were, on average, only slightly happier. Similarly, the paraplegics were only slightly less happy than others. For the most part, they were just as content with life as they had been before that fateful tragedy befell them.

Human beings are truly incredible at adapting to almost anything. Given enough time, both positive and negative changes in our lives can quickly become our new “normal.” When this happens they no longer have a significant impact on our day-to-day emotions. Scientists call this phenomenon hedonic adaptation. It crops up everywhere.

You buy a fancy sports car and its shiny, new features excite you for a while, but months later it brings you little, if any, joy. You move into an old, run-down apartment and its outdated appliances and off-color decor bother you for a while, but months later the annoyance barely registers. You get married to your sweetheart so, of course, you’re blissfully happy for a time. However, a couple years later you have more or less returned to your original level of happiness.

What does hedonic adaptation have to do with motivation? Well, it means that any reward or punishment consistently used to motivate your child will quickly be adapted to and thus rendered ineffective.

For example, let’s say that Margaret, a mother of three, has a son, little Johnny, who isn’t waking up for school. As a Red-Liner, she would go into his room, flip over his mattress, and tell him that if he’s late for school he loses all video games for the day. Well, as you would expect, that’s incredibly effective… the first time. He scurries out the door, and she’s quite pleased with how well it worked. However, with every subsequent mattress flipping after that, she would notice that it doesn’t work quite as well, and eventually it might start producing the opposite effect. She would have to keep upping the ante and putting in more work in order to try to get the same result. She needs to find a scarier stick.

The more Margaret uses this Red-Line approach, the more Johnny goes into Defense Mode and lives in a state of fear. He’s shut down and angry. Any semblance of trust or mutual understanding in their relationship has been destroyed. In fact, he might even start missing school just to assert his independence and regain a feeling of control.

As shown in the Red-Line graph, each new attempt to motivate will produce fewer results, and, in the long-term, will continually require a sweeter carrot or a scarier stick in order to maintain its original effectiveness. As a parent, unless you have unlimited power and resources (doubtful), a Red-Line motivation strategy is simply not sustainable long-term.

By now you may be thinking “Well, of course Johnny would be ticked off and defiant if you punish him like that every day. But what’s wrong with carrots? Aren’t rewards like gold stars and ice cream a more positive and “nice” way to motivate someone?”

To that I say: Yes and no. Carrots come with their own set of issues too. Allow me to illustrate.

Problematic Rewards

A chaotic cacophony of laughter, banging, and shrill exclamations came from every corner of the preschool classroom. Small children were wandering from place to place or talking with their friends, while others sat playing with toys or drawing with markers. A small group of researchers observed the chaos as it unfolded. They had been there for the past several days compiling a list of all the children who typically spent their free-time in the “art corner” drawing with markers. Tomorrow they would be moving on to the next phase of their experiment.

As is usually the case with psychological experiments, the researchers randomly separated their list of artistically-inclined children into three groups. The first group was shown a fancy, “Good Player” award, complete with a blue ribbon, and were told they would receive it as a reward if they drew a picture. The second group of children were not told about a possible reward. They were simply asked if they wanted to draw a picture and when they finished the researchers surprised them with the “Good Player” certificate. The third group was invited to draw a picture and then sent on their way when they finished. No reward promised or given.

Two weeks later, the researchers returned to the preschool to see if rewarding children for drawing had any effect on how the art-loving children now spent their free-time. We would normally expect that those children who were rewarded would draw more frequently now that the behavior had been reinforced, but that is not what happened. The children in the second and third groups (unexpected-reward and no-reward) still spent roughly the same amount of time drawing as they had before. However, those children in the first group (expected-reward) drew significantly less. Plenty of paper and markers were set out and easily accessible, but now that there was no shiny certificate being offered the art supplies seemed to have lost their appeal.

Contrary to what we would expect, introducing an expectation with a contingent reward attached actually decreased the rewarded behavior instead of increasing it. Why? Because human beings are incredibly adaptive. When this new drawing experience taught the children that drawing a picture=compensation, they got the message loud and clear. The children used to draw because they enjoyed it for its own sake (intrinsic motivation). Now they will only draw if they’re expecting to receive some kind of reward.

To give another example, let’s imagine that Margaret, a mother of three, offers to pay her son Johnny an extra allowance so he will finally brush his teeth and wash the dishes. Granted, it might actually work, but in the process, Margaret risks teaching her son that personal hygiene and basic home maintenance are tasks that people should be compensated for. Now it’ll be a lot harder to convince him to ever do it again for free. To give one more example, if Margaret offers her daughter Susie a special treat or a gold star in exchange for cleaning her room, then Susie may stop appreciating cleanliness for its own sake. That will make for a rougher transition when Susie becomes an adult who is expected to maintain a clean house without being rewarded for doing so.

Red-Line tactics tend to increase effort, enthusiasm, and compliance in the short-term, but using them also establishes a long-term pattern of undesired consequences that is very difficult to break out of. Short-term results, long-term consequences.

When to Use Red-Line Motivation

Let me be clear: Choosing to use Red-Line carrots, sticks, and other if/then methods of motivation is not inherently bad and wrong, nor is it always good and right. Red-Line is simply a tool that is uniquely suited for specific kinds of situations.

A hammer is great if you need to drive a nail into wood. It’s less than ideal if you’re trying to perform surgery. The problems arise when you encounter a situation that requires a tool, you look into your toolbox, and you discover nothing but a single, lonely hammer. You’ll probably end up using the hammer because, after all, it’s better than nothing, right?

If, however, you happen to be in a situation that requires a more delicate touch than a hammer can provide, you may inadvertently do more harm than good. This is what happens when Red-Line tactics are used in situations for which they are ill-suited.

What are those situations, you ask? Well, there are quite a few. Red-Line is an extremely specialized tool that is well-suited to a narrow range of circumstances.

There’s been a great deal of research done on this subject and if you want a full-on deep dive then I would recommend you start with the book Drive by Daniel Pink. It’s an amazing treatise written on the subject of motivation.

That said, here’s the short and sweet version.

The “Should I Use Red Line?” Checklist:

1. Is the task boring, monotonous, and/or routine?

☐ No? Don’t use Red-Line!

☐ Yes? Then… maybe. Move on to #2.

2. Does the task have any potential for intrinsic motivation? (i.e. Is this a task that someone might choose to do just because they want to?)

☐ No?- Maybe. Move on to #3.

☐ Yes?- Don’t use Red-Line!

3. Does the task involve creativity or intellectual skill?

☐ No?- Maybe. Move on to #4.

☐ Yes?- Don’t use Red-Line!

4. Is the task related in some way to morals, ethics, and/or some kind of “greater purpose”?

☐ No?- Then...maybe. Move on to #5.

☐ Yes?- Don’t use Red Line!

5. Does the task involve some degree of challenge or variety?

☐ No?- Move on to #6

☐ Yes?- Don’t use Red-Line!

6. Could you change the task in some way to make it more challenging and interesting?

☐ No?- Okay, if you made to this last question and you’ve answered “no” then go ahead and use Red-Line. Just be sure to use the principles taught in Chapters 7 and 8.

☐ Yes? Maybe? Haven't Tried Yet? - Don’t use Red-Line!

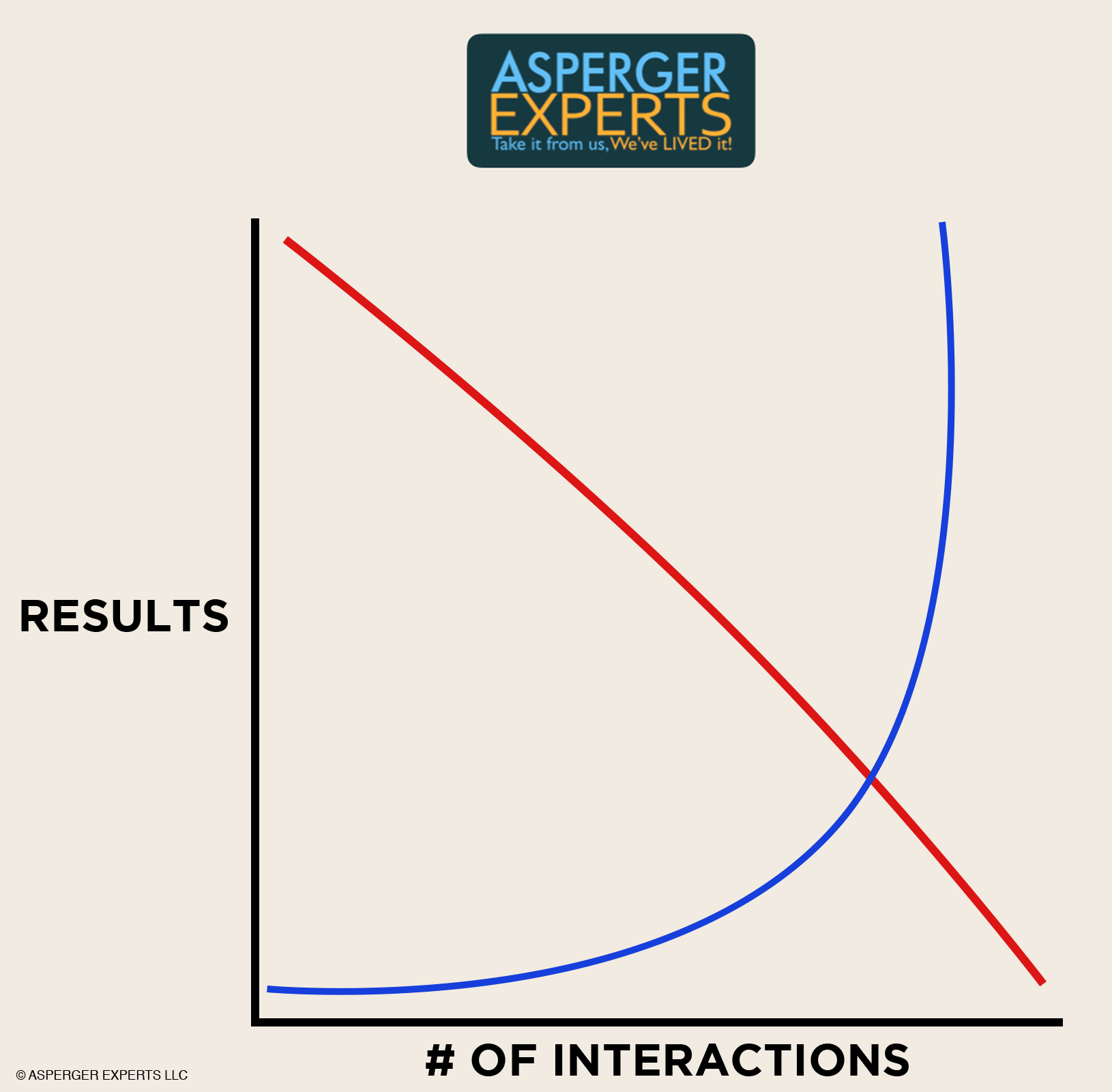

There’s a much better way to motivate your child. Yes, really. It’s called... (drumroll please)... Blue-Line Motivation

You need only look at young children to see our innate human nature in action. They run, play, and explore the world with bright eyes and active minds. They are creative, curious, and purposeful. You see the same thing when you look at adults. People all over the world frequently volunteer time and money, master new skills, and work on projects for hours because they want to, not because their boss tells them to. In fact, people often continue in these pursuits even when it is difficult or painful, so there must be more to motivation than just carrots and sticks. That’s where Blue-Line motivation comes in.

Blue-Line Motivation is all about holistic influence. This means that a Blue-Liner recognizes people as whole, complex human beings who are often intrinsically motivated. They know that people are so much more than animals that simply avoid pain and seek out pleasure.

A Blue-Liner will tap into this innate drive by approaching people and situations from a place of trust and love. They sincerely believe you can and will make good choices for yourself and others. They assume that you’re not necessarily unmotivated. Rather, they are open to the possibility that you might just be scared, stressed, missing resources, or lacking understanding, etc. A Blue-Liner will not try to “force” things to happen, or control you from the outside with carrots and sticks. They will work with and catalyze the natural, intrinsic motivation processes that already exist inside you and within the situation.

However, the Blue-Line path comes with one costly trade-off. A Blue-Liner will need to put in most of the work on the front end, and they will see few (if any) results for the first while. That’s just how the organic process of intrinsic motivation works. Blue-Liners are 100% okay with that because they understand that once you hit the tipping point (i.e. the point where you’re intrinsically motivated and you truly choose it for yourself), then the whole system will become largely self-sustaining.

Blue-Line is essentially the opposite of Red-Line. As more time passes Red-Line requires more and more work, whereas Blue-Line requires less and less. In the end, both approaches to motivation require work and effort. There’s no getting around that. The trap of Red Line is that it looks so easy in the beginning, while it’s actually the more difficult out of the two. The work is still there, it’s just hidden. A Red-liner will undoubtedly find more and more of it as time passes and they slide further down the slope. They have to keep working endlessly and putting in more effort as they attempt to produce the same result. Blue-Line motivation, on the other hand, can get to a point where the parent (or teacher, therapist, whomever) can step back and watch their child soar.

So, rather than insisting on results now (Red-Line), a Blue-Liner will take time to talk to you, listen, hold the space, discuss your personal motivations, and give you what you need. They will trust that, in time, you will make good choices for yourself once you’re ready. Granted, this can be a long process that requires plenty of trial and error, patience, and effort, but it’s all worth it because a Blue-Liner knows this endeavor will pay off in the long-term.

A Red-Liner is a like a carpenter using their tools to shape, manipulate, and polish an inanimate block of wood in order to produce a specific result. A Blue-Liner is more like a gardener, using their tools to adapt the environment and add the necessary resources in order to give the living plant what it needs to grow and flourish on its own.

Let’s go back to the example of little Johnny who is struggling to wake up for school. His mother, Margaret, wants to use Blue-Line methods, so she won’t threaten him, bribe him, or flip his mattress. Instead, she will take an additional ten to fifteen minutes to sit and talk with him, get him a glass of water, rub his back, listen to his concerns about school, and assure him of his own capability. And she’s not lying to him! She knows he’s fully capable of waking up on his own. She doesn’t need to force it to happen. She just needs to remove the blocks and provide nurturing guidance to the innate motivation that already exists inside Johnny.

The Blue-Line approach might mean she needs to wake Johnny up for school ten to fifteen minutes earlier than usual to provide time for her to sit with him and help him wake up. If so, that’s worth it because it’s time well-spent. It might also mean getting a sleep study, or providing the school with a doctor’s note while she takes the necessary days or weeks to work with Johnny one step at a time. In a few months time, Johnny will be waking up on his own, no problem.

The Essential Elements of Blue-Line Motivation

When you’re looking to cultivate the “Blue,” intrinsic, self-sustaining kind of motivation, then there’s three key ingredients you need. They are as follows:

- Capability

- Belief

- Desire

I’ll briefly define each of them, and then we’ll spend the rest of this book exploring in detail how to implement each element.

1. Capability

This may seem fairly obvious, but you’d be amazed how easy it is to forget that this is a factor. If your child does not have the time, energy, resources, emotional capacity, and knowledge/skill, etc. to accomplish the task at hand, then it doesn’t matter how motivating you make it; it’s never going to happen. Or at the very least, it won’t be done properly.

So why do we forget this so often? It happens because of an innate cognitive bias called the curse of knowledge (Yes, really.)

Basically, with the way your brain works, once you know and understand something, it becomes far more difficult to imagine what it was like before you knew it. Later, when you’re teaching that concept or skill to someone else, you may accidentally skip over “obvious” steps, use words and concepts that they don’t understand, or you may just take it for granted that they already know how to do XYZ. You tend to project your knowledge and understanding onto other people and assume that they already know and understand what you do.

For example, here’s an experience related by one amazing mom in our community. We’ll call her son Ron and her partner Bob:

“My partner, Bob, discovered that Ron was still paying our car insurance for an old car he no longer owned. He had $40 auto-deducted from his checking account every month.

When Bob discovered it, he told my son that he needed to cancel the insurance because he was paying for a car he no longer owned. For months, my son assured us he had cancelled the insurance, but still, every month the auto-withdrawal notice would come in the mail.

Then several months later, when we asked him about it yet again, he assured us he had called the insurance company. (He hadn’t, but he was probably embarrassed to admit it.) Supposedly, the insurance company told Ron he couldn't cancel by phone, and that he needed to come in for an appointment. I asked him when the appointment was scheduled for and he gave us a date. To my knowledge, our insurance company is only open for appointments Monday through Friday, but the date Ron gave us was a Sunday. I said nothing.

I later looked up the phone number of the insurance agent, gave it to Ron, and told him all he needed to do was call her. Apparently, that was all he needed. The charge was officially cancelled the next day, and we never saw another notice in the mail.

Turns out, the auto-withdrawal letter that came in the mail did not have the phone number of the insurance agent on it. Bob had told Ron to call the insurance agent, but assumed he would know how to find the phone number. Ron was too embarrassed to ask how, so the whole vicious cycle started: Procrastinate, avoid unpleasant interaction with parents, repeat. Over and over again. Gosh, it took me a while to catch on...

I often have to stop and ask myself, ‘How on earth would Ron know how to do X if he has never done X before or seen it done?’”

2. Belief

There are two kinds of belief that need to be present when fostering Blue-Line Motivation. If either of them are missing, it won’t work.

#1: Belief in Capability

It’s one thing for you to know your child has the capability, but it’s quite another for them to know and believe in their own capability.

If your child genuinely believes that they can’t do math, then any attempts to motivate them, or persuade them that math is really important will only stress them out more and possibly cause them to shut down or get angry.

Alternatively, let’s say you have some serious misgivings about your own competency when it comes to managing your finances. Finances will probably cause you a lot of stress, and it’s unlikely that you will feel motivated to sit down and get it done. While it is entirely possible that you could balance your checkbook without too much trouble if you gave it a try, as long as you continue to doubt your capability you will remain blind to that possibility. You will be more likely to continue procrastinating or you might even give up altogether.

In order for someone to feel motivated they need to feel capable and competent.

#2: Belief in Results

Let’s say that Margaret asks Johnny to do his math homework a particular way and he either 1.) Doesn’t believe doing it that way is even humanly possible, 2.) Does not believe that “Mom’s way” will accomplish his desired result, or 3.) Does not believe that doing the homework and getting that result will ultimately get him where he wants to be. If any or all of those are true for Johnny, then chances are excellent that he won’t want to do his homework the way Mom asked him to.

Again, because of the curse of knowledge it’s easy for Margaret to assume that when she asks Johnny to try a new approach to his math homework he automatically understands exactly how A leads to Z, and he shares Margaret’s world view. She may also erroneously assume that Johnny trusts her completely and wholeheartedly, so when she promises A is going to equal Z, Johnny should immediately take her word for it. Not surprisingly, Johnny, like many other human beings, does not possess that kind of radical, no-questions-asked kind of trust, even with his mother.

So if you have a child that trusts you enough to take a leap of faith blindfolded, then consider yourself blessed (or cursed, depending on your point of view). However, if you happen to be the parent of a child whose trust is less automatic, then it’s important for you to remember that your child may lack the experience, trust, and understanding to know that what you are saying is true. Additional effort will be needed to overcome and move past that block to motivation.

3. Desire

If you’re motivated, then you genuinely want something, right? You have personal, moving, and emotional reasons for moving forward. You see a purpose for acting and believe that the time, energy, and resources you’re expending are worth the expected result.

That’s desire, in a nutshell. Desire is what most people think of when they hear the word “motivation,” and don’t get me wrong, it’s important. However, it’s no less important than the other two essential elements. When all three are present, then motivation is the natural result. When one or even all three are missing, then motivation is scarce.

Eliciting someone else’s passion and desire can be a little tricky because we all want and care about different things. However, when you can successfully stoke a burning desire in someone’s heart, it’s a beautiful thing to behold.

Want More? This is an excerpt from our book "7 Easy Ways To Motivate Someone With Asperger's". Get the whole book here.

Join Our Email List

Get advice, scripts, stories and more sent directly to your email a few times a week.